The woman behind the Kon-Tiki expedition

In 1947, Thor Heyerdahl and his crew sailed the balsa raft Kon-Tiki from Callao, Peru, to the Tuamotu Islands in French Polynesia. The voyage made the six men world famous. However, it was a woman, Gerd Vold Hurum, who was central to the organization of the expedition and held the reins on land. She was the secret seventh member of the expedition. This article is written by Annette Hurum and Reidar Solsvik.

Photo: Gerd Vold Hurum

The Kon-Tiki expedition

The Kon-Tiki expedition was the result of a theory Heyerdahl had been thinking about ever since his stay on the island of Fatu Hiva in the Marquesas in 1938: this group of islands in the South Pacific could not have been populated exclusively by people from the West. It is also said to have been populated by indigenous people from South America.

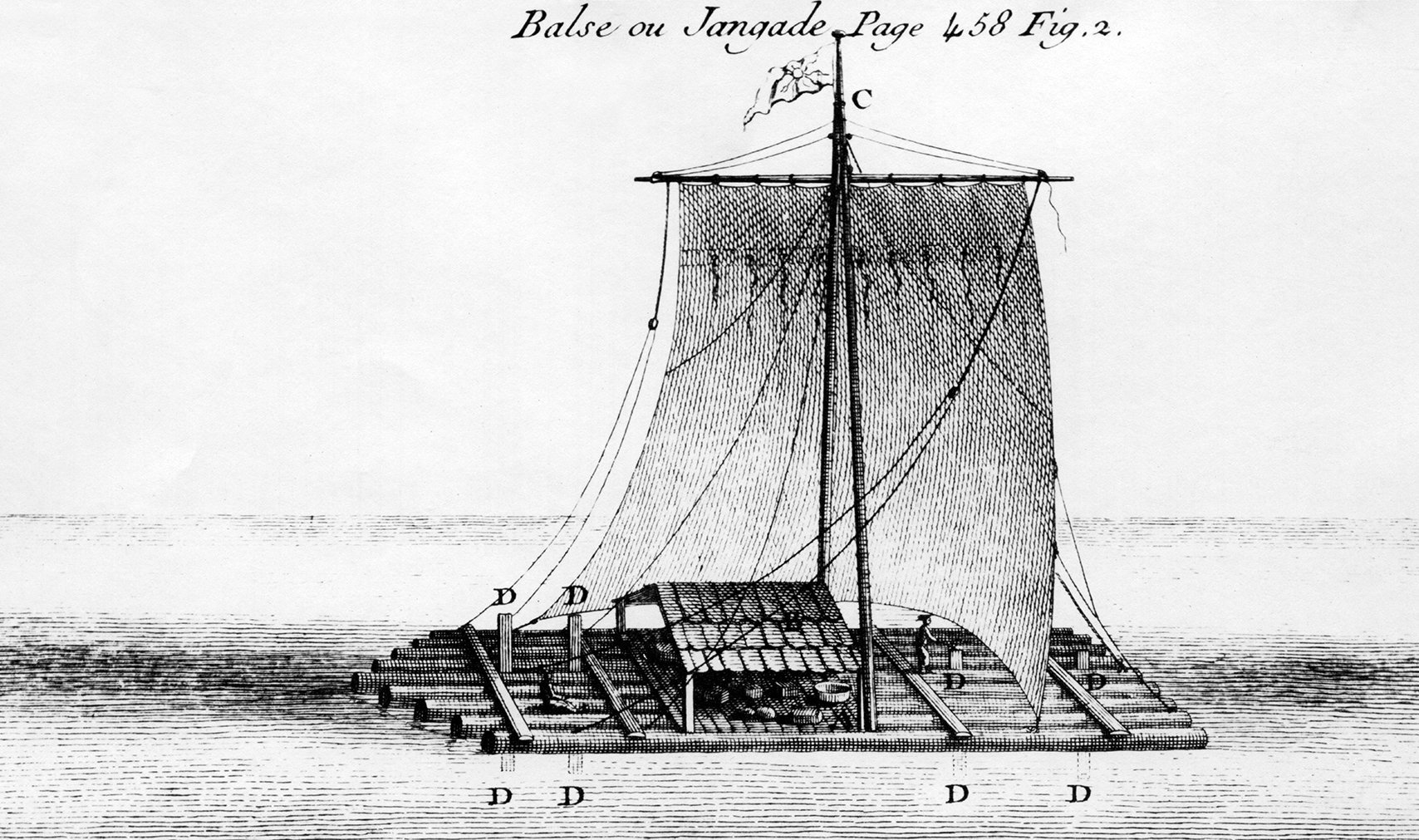

Among the concrete evidence Heyerdahl pointed to was the story of Con-Tiki Viracocha, a native chief who, legend has it, sailed west from Peru into the sunset. On the very coast he sailed from, local fishermen used rafts made from balsa wood. Perhaps this was the type of vessel Con-Tiki Viracocha had used to sail into the Pacific? Drawings of such vessels had appeared in Spanish manuscripts as early as the 16th and 17th centuries.

Heyerdahl presented his theory to a group of leading American anthropologists in the spring of 1946, but they ignored him. An American scientist had already documented that these balsa timber rafts were not seaworthy. Heyerdahl was told. They would soak seawater and sink, or disintegrate, within two weeks. A friendly archaeologist, Herbert Spinden, challenged Thor on this fact, saying, "Sure, look how far you get yourself sailing from Peru to the South Pacific on a balsa raft!"

Heyerdahl accepted the challenge, and began planning the expedition that would take him and his crew across the Pacific on his own balsa raft.

Gerd Vold Hurum - The woman whom the museum forgot

Gerd Vold Hurum was the key person who helped Thor Heyerdahl organize the Kon-Tiki expedition in the winter and spring of 1946-47. In today's terms, she would be called a "project manager". This was Heyerdahl's first expedition, and the way she tackled the task may have taught him some lessons for future projects. Gerd also had the idea of transporting the fleet home to Norway. That Gerd Vold Hurum was a key person in the expedition team has been a well-kept secret for the museum's visitors.

Why hasn't the story of the expedition's 7th member been part of the museum's exhibitions before? The crazy answer is: Because she was a woman!

The Kon-Tiki expedition took place at a time when men were given the leading roles. Women were often relegated to staying in the background, despite their expertise. The men who sailed the raft got the attention, not the woman who helped organize the expedition and held the reins on land.

Gerd Vold Hurum joined the crew during the first hours of sailing the balsa raft, and would probably have signed up for the entire voyage if there had been an option. The Norwegian ambassador in Washington, her boss, had explicitly refused her leave to go on the expedition. He didn't want to lose a hard worker and in the end she was "just" a woman.

Thor Heyerdahl knew Gerd Vold Hurum's qualities when he had chosen her – a woman – over other male candidates as project manager for the expedition.

It took 75 years, but she finally got her rightful place in the Museum.

Raised in Norway

Gerd Vold Hurum was born and grew up in a large, white Swiss-style house in Sæter, Oslo, with an idyllic garden. In addition to flowers and fruit trees, the garden around the house had a small birch grove. The family called the place "Løvås".

Gerd was physically active as a child, and she frolicked in the birch grove at Løvås. Gerd often sat at the top of his favorite tree and did homework. Parallel to this boyish side, she was a very sensitive child.

Skiing and hiking are an important part of growing up in Norway, and these were activities Gerd greatly appreciated. She became a skilled skier and not many men could match her speed. She also unofficially participated in the classic cross-country race, the Birkebeineren, although women were not allowed to participate.

Gerd Vold Hurum in the middle, skiing with his parents Olaf and Oddbjørg and his sister Edith (Photo: Courtesy of Annette Hurum).

Gerd spent summers on his father's family farm near Hamar in Hedmark. At a young age she learned to milk cows and ride horses. Horse riding became a passion she continued for many years. She dreamed of becoming a veterinarian, but her father thought the job was too physically demanding for a woman, and she ended up going to business school.

Resist German occupation and serve the nation

Gerd Vold Hurum in uniform during the Second World War. (Photo courtesy of Annette Hurum)

Gerd Vold Hurum was 23 years old and working for Brage, an insurance company, when the Germans invaded Norway on 9 April 1940. She reacted with every fiber of her being and immediately joined the resistance movement and wrote stencils for the illegal newspaper "We want us a country”.

Gerd soon became an independent operator, with access to a radio transmitter and a mail route to Stockholm, as an agent of the Special Operations Executive. She became a link between the resistance network in Oslo and the Norwegian government in London.

On 18 December 1941, one of her contacts was arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo. Gerd had to flee on foot to Sweden, and then on to England.

Gerd Vold Hurum at the office FO IV.

(Photo courtesy of Annette Hurum)

In London, she became the first female assistant at the Defense High Command's office for special operations, FO IV, led by Leif Tronstad, who collaborated with the British. This office organized sabotage actions in Norway, and Tronstad was the man behind the Vemork raid, where saboteurs destroyed Hydro's production of heavy water at Rjukan.

Gerd became the obvious contact for agents and was perhaps the first in Norway to conduct "debriefings" of secret operations agents.

She became lifelong friends with many of them, including Colonel John Skinner Wilson, head of the Special Operations Executive's Scandinavian division.

The resistance hero makes her stand in a fight for equal pay

After the war, Gerd Vold Hurum was unable to settle in Norway. She therefore got a job as head of encryption at the Norwegian embassy in Washington in September 1945. Here she was to experience a new world and perhaps escape war memories.

Gerd Vold Hurum in Washington, 1945-46 (Photo courtesy of Annette Hurum).

Gerd Vold Hurum had planned to stay at the embassy for at least a year, then take a trip to the west coast of America before returning home to Norway.

Unfortunately, the salaries of the employees at the Norwegian embassy were not among the highest in Washington, or to be more precise, the men were well paid while the women only received slightly more than half of the men's salaries.

The single women had a particularly hard time making ends meet due to the high cost of living, then as now, in the capital.

But when life gives you some self-chosen choices, an unexpected solution can also appear.

Fortunately, the trade adviser at the Norwegian embassy was going back to the "Old Country" and a replacement had to be found. He suggested Gerd Vold Hurum for the position. Even better, while Gerd earned $200 in his current job, the commercial consultant earned $350.

The ambassador immediately agreed when he was asked if Gerd Vold Hurum was a good choice for the job. She was to become the first female commercial adviser in the history of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Only the question of wages remained, and then presenting the matter to the ministry and getting their approval.

But now the foreign service's long and "proud" traditions began to interfere in the matter. The Charge d'affaires, who was responsible for filling the position, foresaw that proposing equal pay for equal work would not be proper diplomatic procedure. Gerd Vold Hurum's predecessor was a man, and the women who worked for the embassy did not get such high numbers. The "smart" solution was to get her the job and give her a raise afterwards. At least this was his argument. Accordingly, he proposed a monthly salary of $290. He even thought he was checky for asking so much. After a good night's sleep, the man had a severe anxiety attack and he reduced his proposed salary to $275. But the doubts still gnawed at him and he called Ambassador Morgenstierne, who agreed. "Not higher than $250 dollars!" The faithful office ladies who had worked up to 28 years at the minimum wage embassy could be envious.

When the job offer came from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the proposed monthly salary was cut by another 50 dollars to only 225 dollars. Gerd Vold Hurum, who was proud and had no intention of selling herself cheap, told the ambassador that she would not take the job unless she received equal pay for equal work. When she returned to the office, she booked a flight home to Oslo a few days later, on 6 December 1946.

Thor Heyerdahl and the Kon-Tiki expedition were to benefit from Gerd Vold Hurum's unfortunate case. Ambassador Morgenstierne ordered her to remain in the position of head of encryption until a replacement could arrive from Oslo and be trained. The Kon-Tiki boys willingly made her a project manager and part of the Kon-Tiki family, benefiting from her professionalism and first-class work ethic that her country did not appreciate highly enough.

Gerd Vold Hurum, Torstein Raaby, Thor Heyerdahl and Erik Hesselberg, in Callao during the final preparations for the Kon-Tiki expedition.

The woman who could fix everything

The phrase "A man's world" sometimes refers to the fact that established networks of men often help other men create carriers. But when it really mattered, it was a woman with an extensive network and great organizational talent who helped Thor Heyerdahl. Her contacts from her work at FO IV during World War II and her time in Washington gave Gerd an uncanny ability to solve urgent problems that challenged the organization of the expedition.

The expedition had been offered to test equipment for the US War Department, but Heyerdahl wanted to meet the decision-makers in person, to persuade them to quickly approve the offer. Others had refused help when they heard that the primitive balsa raft would sail alone across the Pacific. Heyerdahl turned to the rich Norwegian-American Georg Unger-Vetlesen, a key figure in the intelligence work during the Second World War and later one of the architects behind the airline SAS. Vetlesen identified General Hoag and Colonel Clark as key figures in the Quarter Master Division of the Armed Forces, although he did not know either of them personally: "You need someone to introduce you."

Heyerdahl despaired, but was immediately encouraged when the driver of the new Ford that took him back to Washington, Gerd Vold Hurum, said she could handle the task. The very next day, General Hoag was sitting in Vold Hurum's apartment with the Kon-Tiki boys. Colonel Clark came by a few days later.

Gerd Vold Hurum drives the Ford she had bought for her brother-in-law

(Photo courtesy of Annette Hurum).

When the expedition arrived in Peru and they needed help from the authorities, Gerd charmed General Reveredo with her intellect and efficiency so that a car and driver were made available for the expedition. When they encountered problems, Thor Heyerdahl always said with optimism in his voice: "Let's send Gerd!"

A comfort for the families

The hardest part of Gerd's job began when she returned after being aboard the raft for a couple of hours to Callao, in a sailboat that belonged to the editor of Lima's biggest newspaper.

The Kon-Tiki expedition sent radio messages to the newspapers during the voyage. Gerd Vold Hurum's task was to convey the messages to the press and partners. However, she quickly realized how important it was to keep the families of the crew informed.

The Kon-Tiki radio station at Raroia Atoll in the Tuamotu Islands.

In today's age, this is an easy task.

In 1947 all letters had to be typed, two or three at a time. Since they became so popular, she had to produce 14 copies while managing her full-time job at the embassy.

Gerd also encouraged the families to update her on daily life to lift the boys' spirits.

This was transmitted to the small radio aboard the raft.

Gerd was never actually paid for the work she did for the Kon-Tiki expedition. Fortunately, she was paid for the work she did at the embassy.

She considered being part of such a historic event an incredible experience.

How did the museum come about?

How did the Kon-Tiki raft end up in a museum? Thor Heyerdahl went on the expedition to prove that old Peruvian balsa rafts were capable of crossing the ocean. This he had proved, and initially intended to leave the wooden raft on Raroia Island as a testimony to its seaworthiness. The expedition also did not have the funds to pay for transport home.

It was Gerd's idea that the fleet should be exhibited. Perhaps the ticket sales can earn some hard-earned money to cover expedition expenses. The Kon-Tiki raft was towed to Papeete and moored along the promenade quay. Gerd got the job of arranging transport to the USA, and she was able to arrange for the cargo ship M/S Thor I to call in Tahiti.

In America, Gerd tried to arrange for Kon-Tiki to be exhibited in a local park in San Francisco. But even in America, there are obstacles for entrepreneurs. They had to pay rent for the exhibition space and wages for people to guard the fleet. In addition, a financial guarantee had to be provided in advance for the fleet to be removed afterwards. Without fresh cash, this was impossible. Gerd again had to organize transport. This time to Oslo.

Knut Magne Haugland, who supported Gerd's idea, took on the job of collecting money and building the museum once back in Oslo. On 15 May 1950, the Kon-Tiki Museum opened its doors on Bygdøy and within a few years became one of Norway's most popular museums.

Gerd's life after the Kon-Tiki expedition

In 1950, Gerd met Sven Hurum, a businessman and Norwegian honorary consul in Manila in the Philippines, who was on holiday at home in Oslo. The couple fell in love and married 15 days later. After a few years in the Philippines, the family moved to Montreal in Canada, where Sven Hurum established an office for the Norwegian shipping company Wilhelm Wilhelmsen. Here they had two children, Sven Olaf and Annette. Gerd and Sven Hurum possibly had their best years back in Oslo after they retired in 1977.

In Montreal, she became restless as a housewife, and started her own company selling Norwegian gift items. But when she got the news that some Canadian medical researchers intended to organize an expedition to study the health of people on Rapa Nui or Easter Island, she again volunteered to help. It was the medical expedition to Easter Island, METEI, 1964-65.

In 1967, Father Sebastian Englert, the Catholic priest who had helped Thor Heyerdahl's Norwegian archaeological expedition on Rapa Nui in 1955-56, came to America and Canada. He fell ill and Gerd Vold Hurum followed him back to the island.

Without Gerd Vold Hurum, the Kon-Tiki fleet might not have sailed from Callao on 28 April 1947. Thor Heyerdahl and his crew members knew this well. For them, she was the 7th member of the expedition.

Drawing of crew member Erik Hesselberg in Gerd Vold Hurum's copy of "Kon-Tiki. On a raft over the South Sea".

(Courtesy of Annette Hurum)